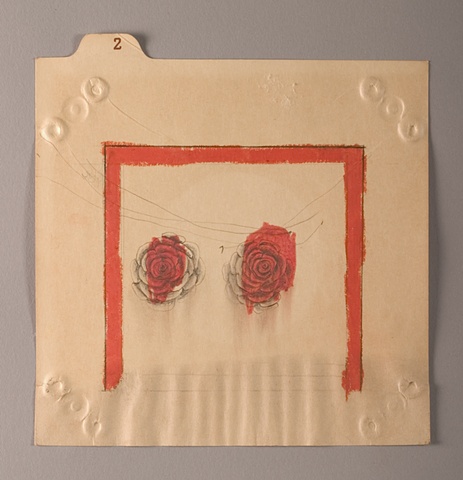

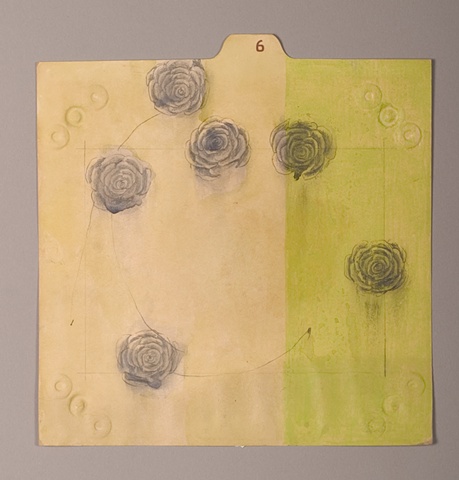

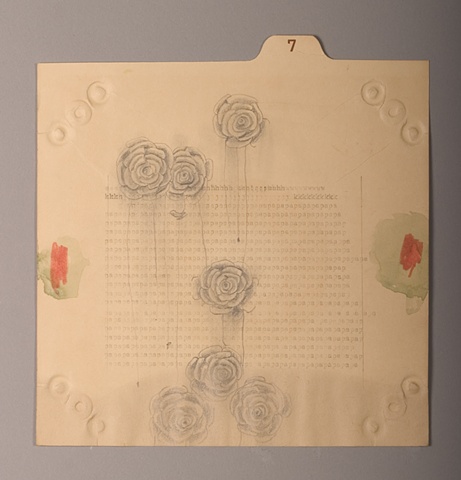

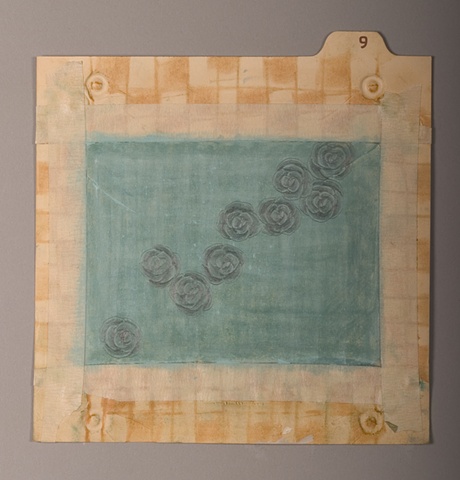

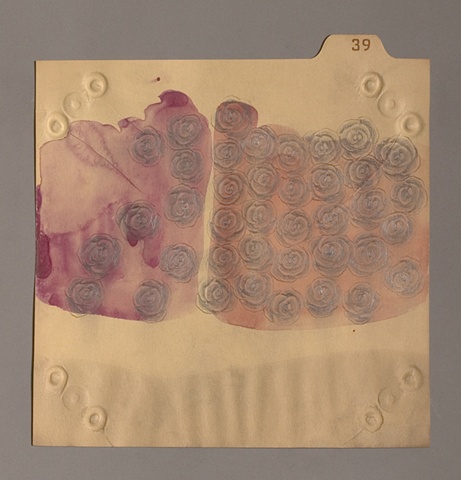

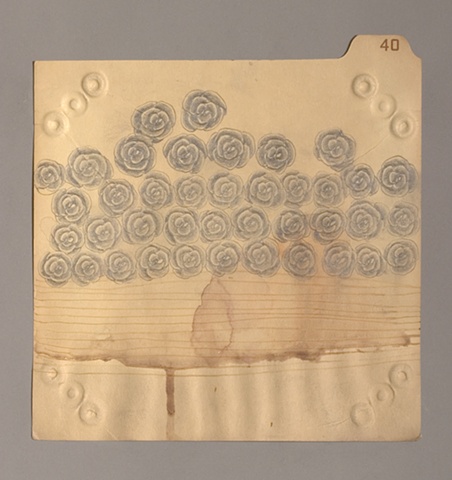

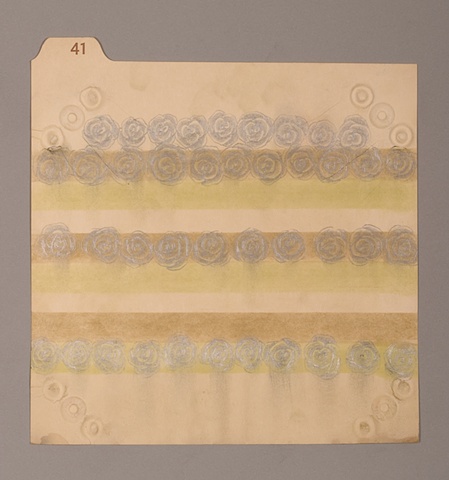

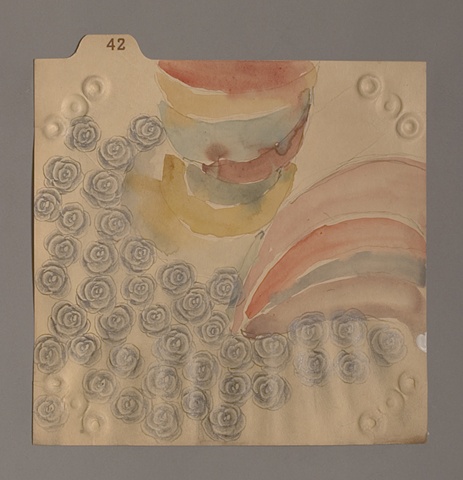

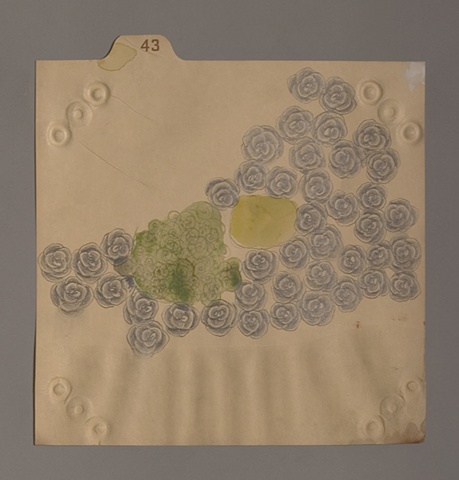

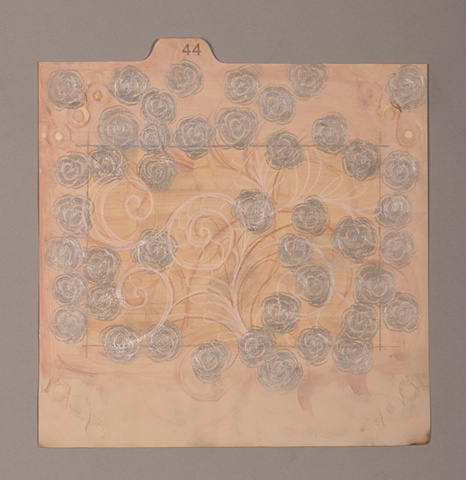

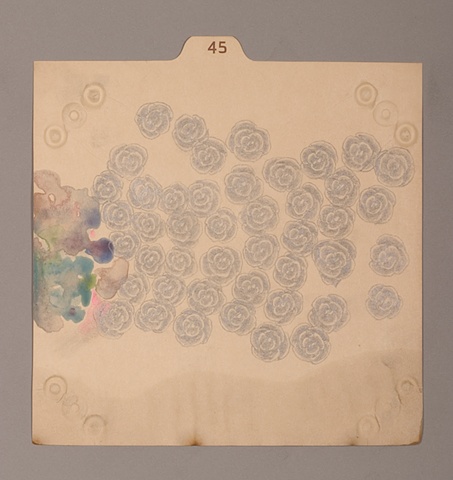

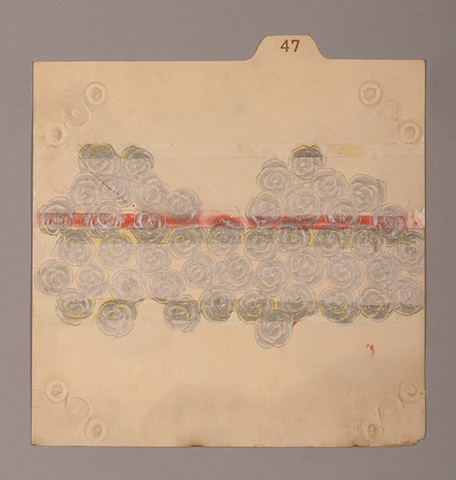

for annabelle

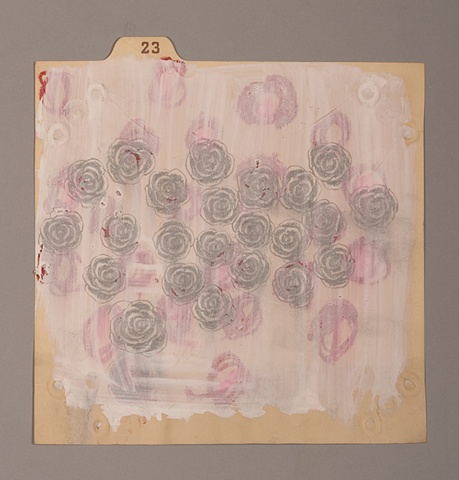

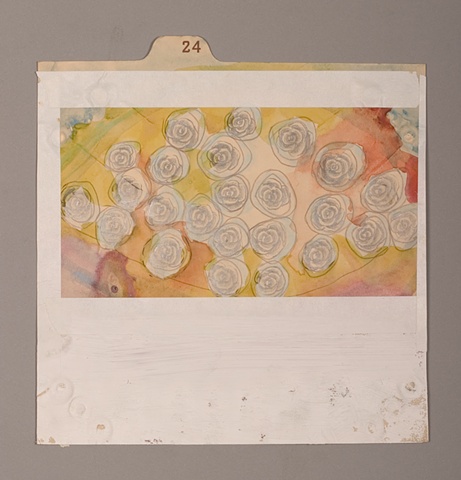

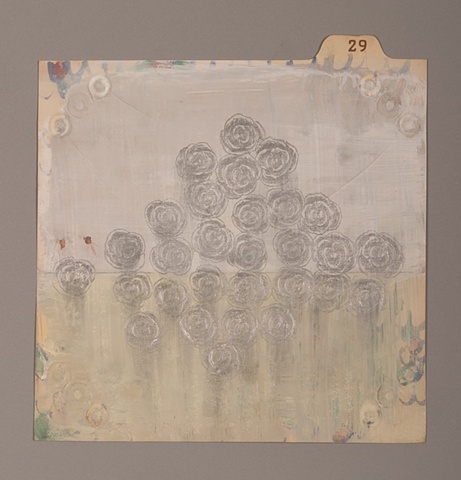

The memory I hold of my grandmother is stoic, clean, and kind. The intimate thoughts of her are personal and visceral. Helping me wash my hands in her bathroom, using a hard scrub brush to remove the dirt from under my nails the way a nurse could only do, slightly painful and abrasive. The woman who became a nurse on the GI bill working night shifts without complaint always wearing her clean white pressed uniform, white tights, white hat, white shoes. The woman who knew every pill they handed her at the hospital while ill.

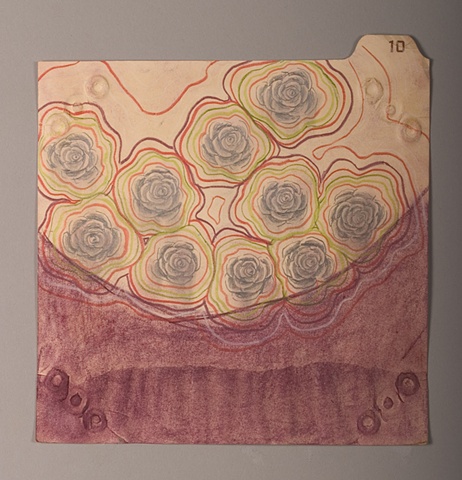

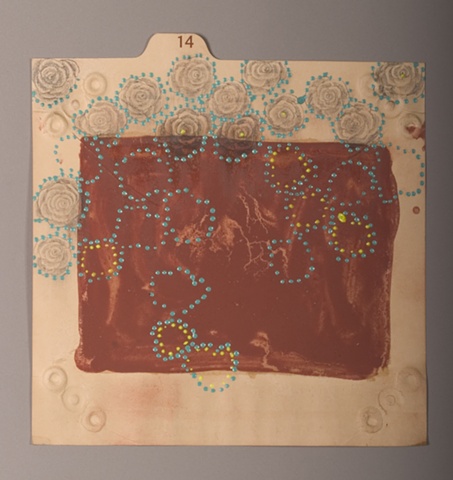

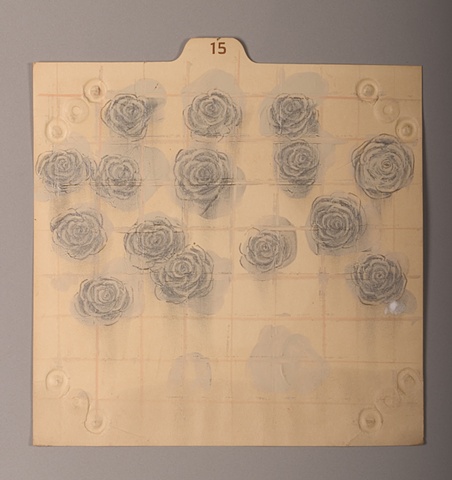

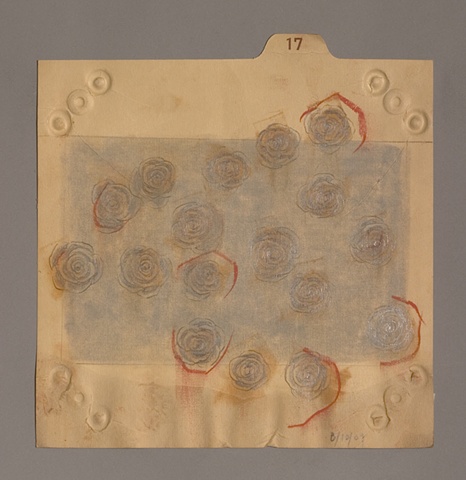

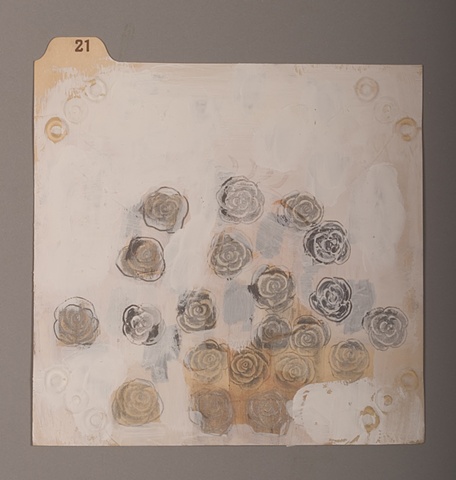

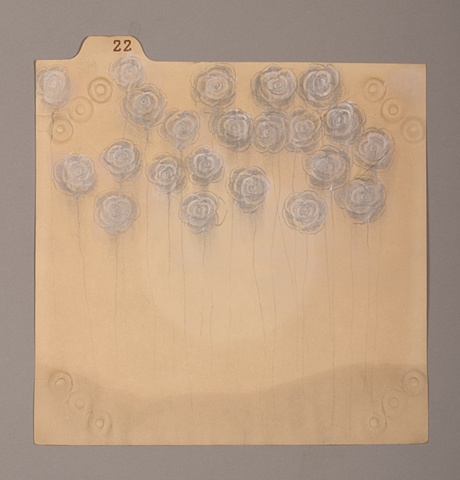

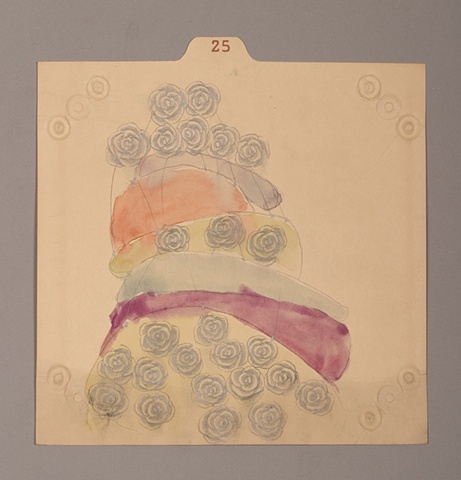

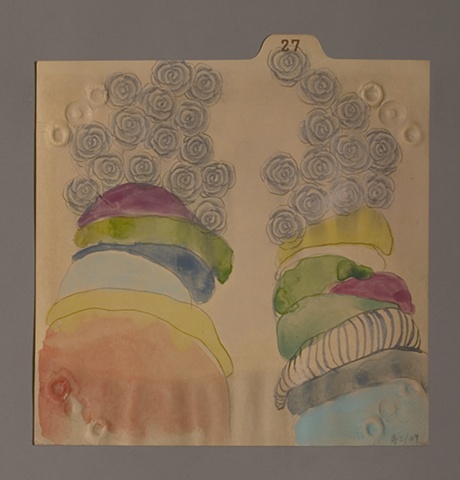

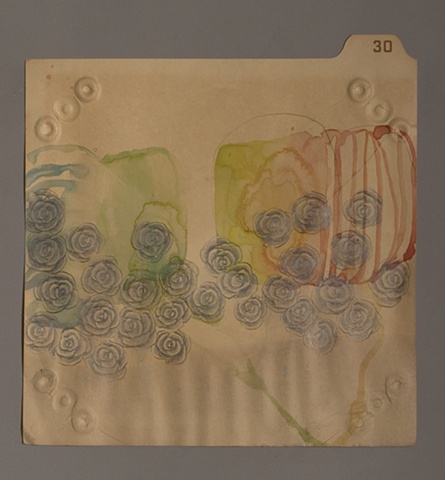

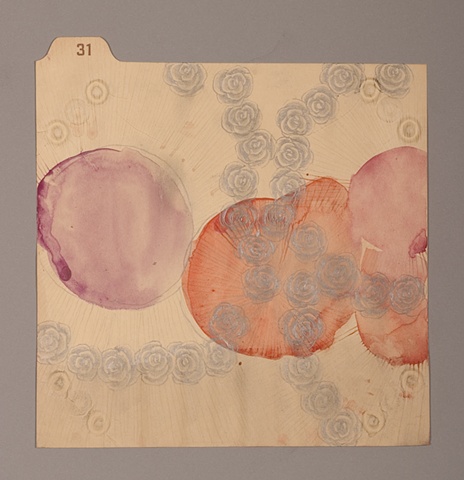

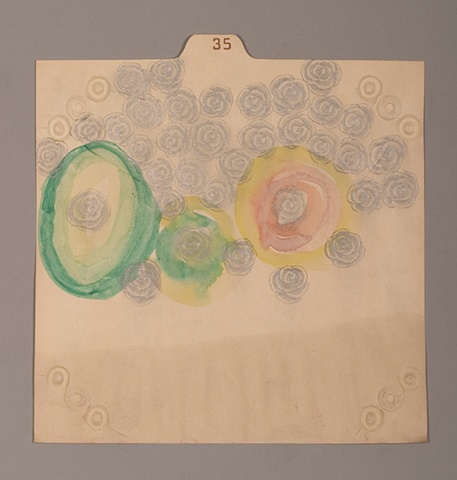

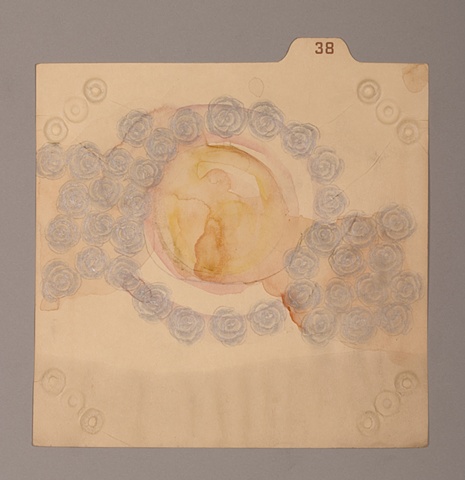

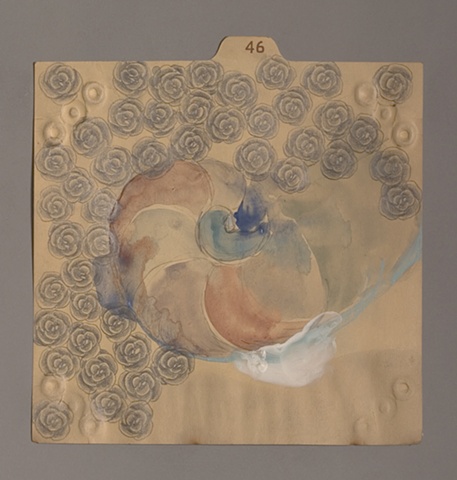

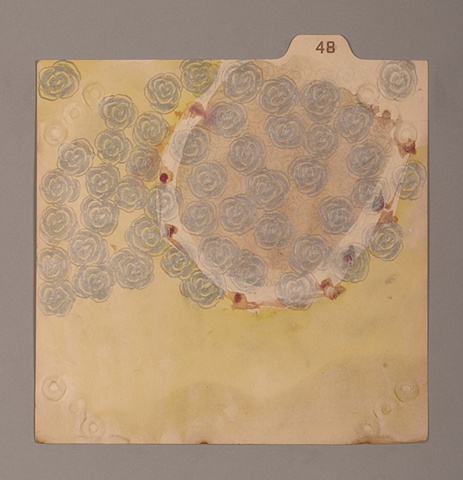

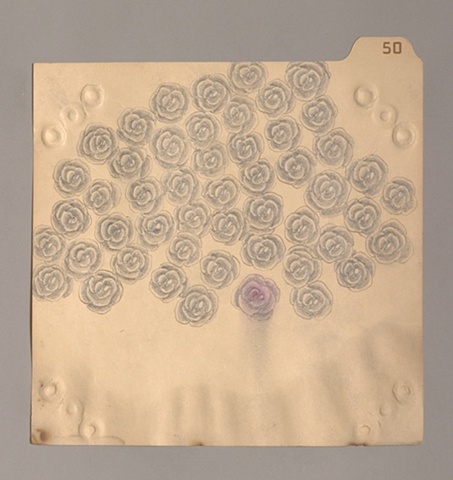

Constant doing, repetition, and personal ritual would guide me through my own grief. This body of work began as an exercise to deal with the cancer my grandmother was facing. In an effort to heal I began collecting sticks by hand, a process learned by observing my father. Not wanting to dispose of these limbs, I cast, bandaged, and mended them in an effort to heal and bring new life to once discarded life. After casting I would scrub and sand. The bones in the work were collected in the open landscape of Montana, where the sight of a carcass is common and natural. In contrast, seeing a carcass in a more densely populated space becomes visceral, ugly, an obstacle.

It is transformative quality seeing a bone in the landscape and that reverence I wanted to bring to this work. It has been a necessity to constantly “do” in an act of healing. In a culture where grief is often over-looked, denied, and repressed I found my ritual and rite of passage. It was not an effort to completely mend, rather honor someone who set a precedence of living, giving and sharing.